In an alternate history work of fiction, what would be a good way to rationalize/justify a world in which there is no usage of fossil fuels?

I think in this alternate history / worldbuilding idea, the physical matter still exists - there is coal, oil, etc, in the earth, but I am wondering if we can come up with a satisfying reason why humans could not make use of anything more efficient than peat in production. Is there a scientific-sounding explanation that could be given to make a world in which coal and oil are useless in industry?

I have been reading “The Future is Degrowth” and “The Origin of Capitalism” and that is what inspired this. The first book says something along the lines of “the capitalism we know, of endless accumulation, is fundamentally a fossil capitalism”. The second book makes a very convincing case that what existed in England centuries before fossil fuels was already distinctly (agrarian) capitalist. Interest in everyone’s thoughts and ideas about how this could be constructed, and what sort of events could play it out in the cradle of capitalism but also worldwide.

If we are looking for a point-of-divergence within recorded history, there’s probably not going to be a scientific reason humans wouldn’t be using fossil fuels. That doesn’t mean there couldn’t be other, less-scientific reasons, like a complete reshaping of 19th century society, or an industrial revolution happening centuries earlier that is more dependent on hydro-power than coal.

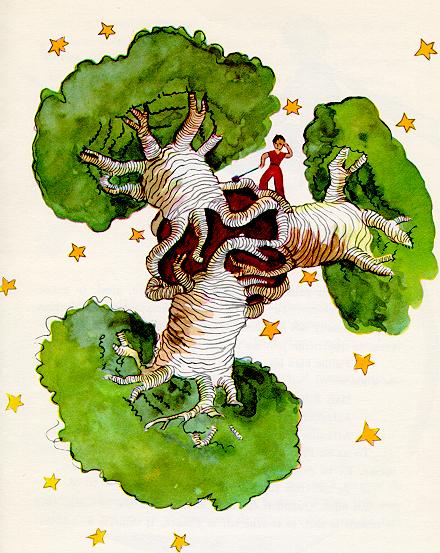

While successful socialist revolutions are interesting (it’s the main theme of my current writing project), a equally intriguing idea would be to start the industrial revolution in the first century CE. Where Hero of Alexandria1 was building rudimentary steam engines not long after the founding of the Roman

PrincipateEmpire, maybe he finds a semi-fictional patron2 that is looking for more practical applications for this steam engine, for example: farming, textiles, or papyrus production. Then, while using the predictable flow of the Nile for hydropower, industrialisation slowly mechanises the province and spreads from there.Another fun companion idea would be to have this new industrialisation rise alongside and compete with early Christianity. As one of the main draws of the latter was its relatively good treatment of the poor4. But, they view the new technology as a further sign of the coming apocalypse. While the farmers and other labourers are just enjoying not having to work so hard for food and clothing, leaving them free for more creative endeavours. This could create some conflict for a story, in addition to the general anti-Roman-state viewpoint of the Christians5.

1 Here’s a fun little write-up on a gaming website of all places.

2 This person could release the technology for the hydro-power engine for free, à la Tim Berners-Lee and the world wide web. Rather than waiting for people to procure machines and spread industrialisation through more creative methods3.

3 For more information on this topic see: Trade Secrets: Intellectual Piracy and the origins of American Industrial Power by Doron Ben-Atar

4 “… by the time …[of] the late first or early second century organized poor relief was no doubt underway in parts of the Christian world, conducted by either local workers specifically designated for the activity, or by volunteers who heard the cry of the poor.” from Yale

5 "The Christian movement was revolutionary not because it had the men and resources to mount a war against the laws of the Roman Empire, but because it created a social group that promoted its own laws and its own patterns of behavior. … Christianity had begun to look like a separate people or nation, but without its own land or traditions to legitimate its unusual customs."6 Wilkens, R. The Christians as the Romans saw them pg. 119

6 Furthermore, early Christians refused to participate in politics, religion, and to fight in the empire’s wars.