- 13 Posts

- 44 Comments

3·4 days ago

3·4 days agothis is getting to hawk tuah levels of stupidity

because muslims have a book with instructions from a being that lives in outer space that tells them that sexual deviancy is morally reprehensible and shouldn’t be encouraged or allowe

11·5 days ago

11·5 days agoi didn’t say the author is 10, i picked a random age

i could have said really 6 years olds stressing over property prices? yeah right

11·6 days ago

11·6 days agothe original article:

Labor’s social media ban will not benefit young people

12·6 days ago

12·6 days agoand you believe the majority of kids are having one meal a day?

12·6 days ago

12·6 days agoban is for under 16s

i also strongly doubt that social media is doing much to help the kids who are stressing about those things

35·6 days ago

35·6 days agowas this written by ai?

The statistics show that much of young people’s declining mental health is caused by social issues such as the cost-of-living crisis, housing insecurity and fears about the climate emergency, much of which can be sheeted home to government policies.

really 10 year olds worried about cost of living and housing??

11·8 days ago

11·8 days agoteslas are everywhere here in brisbane, can’t really go anywhere without seeing one, byd starting to make inroads as well

2·8 days ago

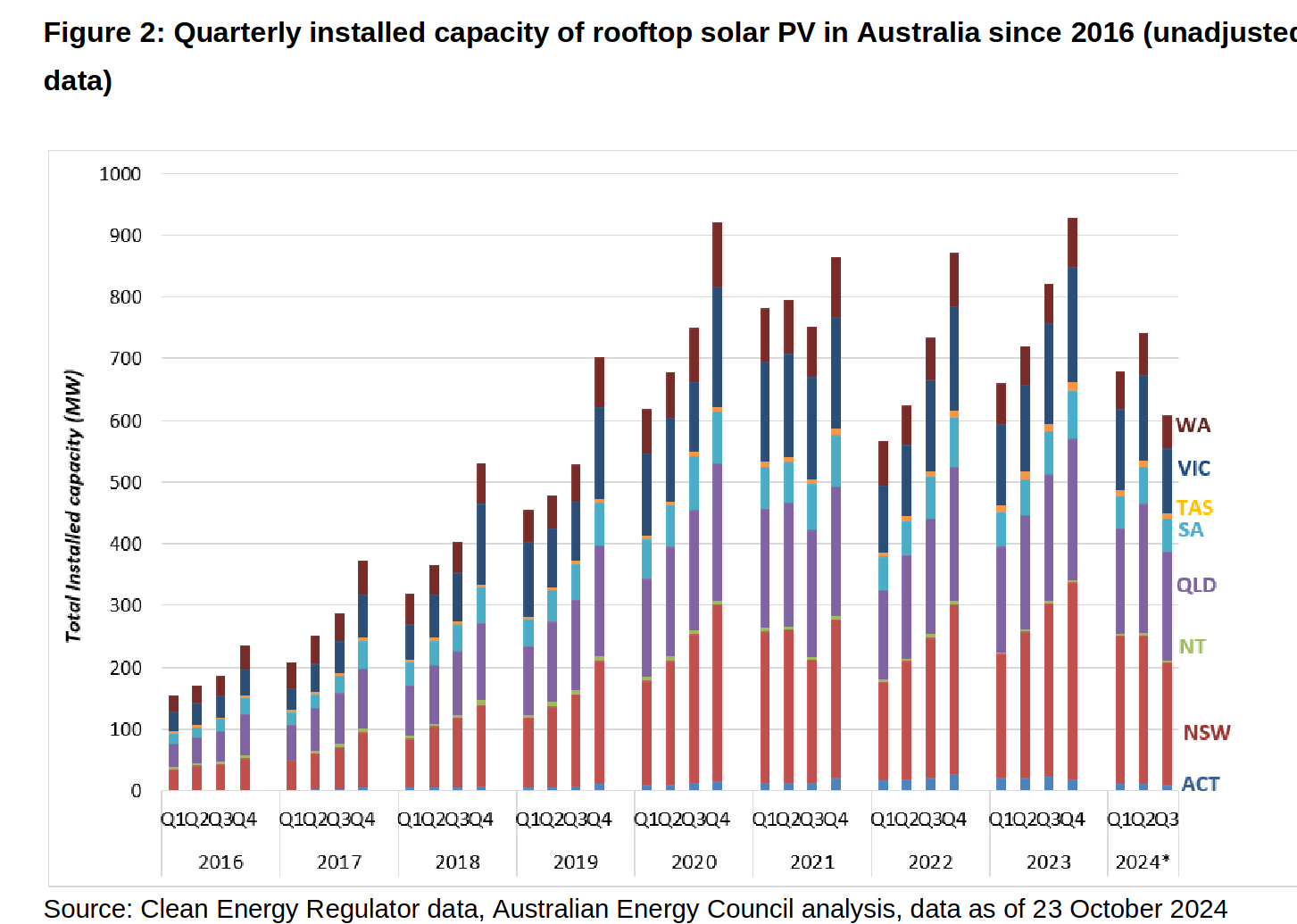

2·8 days agowould love to see if there is something like this for Queensland

0·10 days ago

0·10 days agoi’ll admit i don’t like the drag queen storytime, just doesn’t sit right with me

tbf i probably wouldn’t like tradie storytime or ceo storytime either, just seems…suspicious…but at the same time parents are more than welcome to just not go, not sure where the issue is

the teenagers attacking gays is just maddening, i wonder where they are getting it from

Just let people live how they want to live!! I don’t understand why it’s so complicated for Christian fundies to understand that.

What makes you think Christian fundies have ever been about “Just let people live how they want to live!!” which appears to be a 1970’s hippie inspired slogan?

Almost the complete opposite of what Christians and Jews and especially Muslims are about.

0·10 days ago

0·10 days agoAccording to Ed Husic, the Minister for Science, Indigenous Australians were “the nation’s first scientists”, whose insights, obtained “through observation, experimentation and analysis”, rested upon “the bedrock of the scientific method”. Nor is Husic alone in making those claims. Thanks to generous taxpayer funding, a burgeoning industry promotes “Indigenous science” in venues ranging from schools to universities.

But to call Indigenous knowledge “science” grossly misrepresents the nature of the scientific enterprise that emerged from the intellectual revolution of the 17th century. The error is neither innocent nor harmless: it both devalues that revolution’s achievements, which made Western science into an engine room of human progress, and projects a romantic, yet fundamentally condescending, vision of Indigenous culture.

To refer to the changes that occurred in the 17th century as a revolution is not to ignore the solid foundations on which they built. The notion of science as an activity that, in the words of Diogenes Laertius (180AD-240AD), seeks to “understand things as they are” through the “rational explanation of phenomena”, was well known in classical antiquity and persisted into the Middle Ages.

However, the great thinkers of the 17th century radically transformed what Kant later referred to as science’s “regulative principles”: that is, the rules that distinguished science, as an activity and as a body of knowledge, from mere knowhow. At a fundamental level, the transformation involved a dramatic change in the conception of the cosmos.

In effect, the 17th century upended the Aristotelian view of nature, which claimed that the basic properties of matter differed in the various parts of the universe. Nature, the proponents of the new science argued, was homogenous, uniform and symmetrical: matter was the same throughout the universe, governed by the same causes or forces. Moreover, those forces were mechanical: the very essence of science lay in uncovering their laws of motion.

In turn, those presuppositions of regularity and homogeneity underpinned a change that proved momentous: the rejection of Aristotle’s prohibition on metabasis, that is, on the transposition of methods from one discipline to another.

The sciences, said Rene Descartes in 1637, could not progress “in isolation from each other”; they all had to advance, and could only advance, by adopting common methods, centred on developing mathematical representations of the phenomena they were seeking to explain.

And the test of those representations had to be both analytical and empirical: analytical in terms of mathematical correctness; empirical, in that it had to be shown that the representation could be used to recreate the phenomenon.

Truth, in other words, was “fact” in the Latin sense of the word: that which can be done or made. As Giambattista Vico summarised the new thinking in 1710, “verum et factum convertuntur” – the true is that which can be converted into fact, ie, can be done in practice.

That is why Newton, to prove the existence of a centre of gravity, devised the famous experiment of the rotating bucket filled with water. It is also why Francis Bacon resuscitated the Greek term “praxis” – the unity of theory and practice – in the Novum Organum (1620) to describe the “scientia activa” of experimentation, which, far from diverting study from its object, was the sole means of “augmenting” it.

Those contentions, and particularly the emphasis on factual replicability, provoked vociferous objections from the so-called Occasionalists, who feared the implication that we can master the making of the universe in the same way as does the creator. However, the pioneers of the new science were cautious in their claims. Yes, mathematical techniques could accurately model limiting cases, such as motion in a vacuum; but they only approximated actual outcomes. And it was improper to speculate about the underlying causes of phenomena beyond what could be directly observed and experimentally verified.

Hence Newton’s great outcry, “hypotheses non fingo”, “I feign no hypotheses”, regardless of how much superficial completeness adding unproven hypotheses might give his system.

That intellectual modesty opened the road to a recognition of the uncertainties inherent both in the actual operation of the laws of motion and in their testing. In what ranks among humanity’s great breakthroughs, Blaise Pascal’s work on probability theory, and Thomas Bayes’ formalisation of inductive inference, set the basis for the systematic hypothesis testing that allowed Western science to progress at an unprecedented rate.

But that rate of progress also reflected another crucial feature of the intellectual revolution: its openness. Traditionally, true knowledge had been seen as esoteric, handed down, within closed circles, from one generation to the other and validated by the weight of inherited authority. By the end of the 17th century, that notion had been utterly discredited.

Instead, theories, models and experimental results were widely published, discussed and contested, vastly accelerating their development.

In short, what defined Western science and made it absolutely unique – and uniquely powerful – was the tight integration of formal methods, rigorous verification and public replicability. Additionally and crucially, it was self-aware, devoting ongoing attention to the regulative principles with which scientific practice had to comply.

The contrast even to China could not have been starker, helping to explain why China’s initial advantage in virtually every area of technology stalled and then collapsed. As for the chasm separating science from Indigenous knowhow, with its secrecy, its anthropomorphic explanations and its reliance on the authority of elders, it can only be measured in light years.

However, Husic’s claim is not just absurd. It is, like Bruce Pascoe’s fantasies about settled agriculture, deeply patronising. Husic plainly does not grasp the complex of ideas that comprise the scientific method. But he clearly believes that Indigenous culture, if it is to be respected, must be cast as an anticipation, if not a mirror, of Western culture. If we had science, whatever that may be, they must have had it too – and many centuries before us.

One might have hoped that the decisive refutation of Pascoe’s contentions by Keryn Walshe and Peter Sutton would have laid those views, and the broader attitudes they embody, to rest.

Yet they live on, thanks, in part, to sheer ignorance. Also at work is the conviction that historical accuracy and intellectual honesty matter less than “celebrating” Indigenous culture – a conviction that, far from promoting science, offends the unbending commitment to the truth that is science’s very essence. Significant too is the now ingrained hostility to the Western achievement, and to the scientific spirit, which is among its glittering jewels, with it.

However, spinning fairytales is no way of convincing the community, and young people in particular, of science’s vast potential. Nor will it do anything to reverse the continuing fall in the number of high school students taking core science subjects. Having a minister for science who knows what the term means will certainly not solve those problems. But it would be a sensible place to start.

Henry Ergas AO is an economist who spent many years at the OECD in Paris before returning to Australia. He has taught at a number of universities, including Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, the University of Auckland and the École Nationale de la Statistique et de l’Administration Économique in Paris, served as Inaugural Professor of Infrastructure Economics at the University of Wollongong and worked as an adviser to companies and governments.

0·10 days ago

0·10 days agowe are here to fight for our rights and equality - which we still don’t have

What rights don’t you have?

0·13 days ago

0·13 days agoI don’t know if you mean to come across like a profound philosopher whos stumbled onto a great secret that makes all economics? digital currency? fiat currency? as dumb as a literal ponzi but if you could get your point across without being vague as hell that’d be great.

0·13 days ago

0·13 days agoso your issue is with fiat money and basically the entire modern monetary system… nice

I still don’t understand how a literal ponzi is as stupid as fiat money but you do you

1·14 days ago

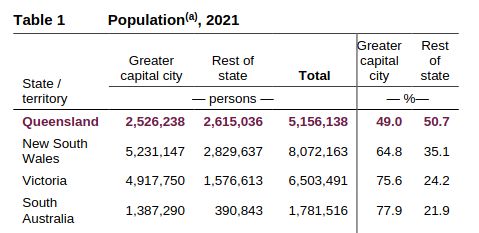

1·14 days agoThere’s a lot more to it than just economies of scale, firstly Queensland has a huge rural population, as a percentage of population it’s the only state outside of Tasmania that has a bigger rural population than living in the city

https://www.qgso.qld.gov.au/issues/11951/qld-compared-other-jurisdictions-census-2021.pdf

Coal power and mining represent jobs for rural people because renewables largely don’t need anyone to maintain them or dig stuff up out the ground.

This means there has obviously been a laggard effect with rural jobs adding an extra dimension to our renewables push by making it a political issue, hence why we have been delayed in making world leading progress compared to a place like SA.

The friction of rural jobs and wanting to push for renewables resulted in Labors “Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan” https://www.energyandclimate.qld.gov.au/energy/energy-jobs-plan as a way to push renewables and get rural people jobs at the same time, the “Queensland super grid” as you can see goes quite far out into regional areas: https://www.hpw.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/49241/rez-roadmap-a3-poster.pdf

Despite this there are some downfalls with renewables and it impacts SA heavily, without grid firming you have far more volatile electricity prices

South Australia price spikes in Q3 2024

In addition to the NEM-wide volatility events discussed in the previous section, South Australia experienced more extended periods of price volatility resulting in a regional cap return of $77/MWh, well above other regions and contributing 49% of the total NEM cap return. These events were driven by a combination of factors including cold evenings, low wind conditions, and network outages limiting Heywood interconnector flows or constraining some generators in the region at times.

This seems like a constant SA experience compared to other states which is probably why your batteries made the most money arbitraging it:

While all regions experienced growth in energy arbitrage revenue, Victoria and South Australia stood out, with energy arbitrage revenue for Victorian batteries increasing by $13.9 million (+175%) and for South Australia by $18.0 million (+319% ).

QLD isn’t exactly sitting back doing nothing, we have a large amount of grid firming going in:

Proposal to develop a pumped hydro energy storage (PHES) project to supply up to 2,000 MW electricity for up to 24 hours (resulting in a storage capacity of 48,000 MWh)

Development of a pumped hydropower energy storage project in the Southern Queensland renewable energy zone with the capacity to generate up to 400 megawatts (MW) of continuous electricity for 10 hours per day, and a battery energy storage system with a capacity of 200 megawatt hours (MWh)

Pumped hydroelectric energy storage (PHES) and transmission project with a stored capacity of up to 750 megawatts for approximately 16 hours for a 24 hour period.

Converting the Mt Rawdon gold operation into a sustainable low cost, large scale pumped hydro power station

We’re a bit lucky in that thanks to SA we have been able to see that going all out on wind farms and solar isn’t a winner, you need grid firming batteries just as much as you need electricity generation.

I have to say it’s very odd that despite SA having constantly much higher price volatility and the need to smooth it with firming the Labor government dropped the battery rebate?

Industry stunned as SA Labor dumps home battery subsidy and solar switch program

Still very confused about that one, what better way to help people in SA pay less for power and assist the grid than with home batteries?

Despite all the headwinds and with the “economies of scale” we obviously have more solar installed than SA:

New South Wales and Queensland continue to lead the way in rooftop solar capacity and installations. New South Wales, with a capacity of 6.232 GW, holds the top spot, closely followed by Queensland with 6.082 GW. In terms of installations, Queensland leads the nation with a total of 1,015,589, while New South Wales follows closely with 963,524 units.

https://www.energycouncil.com.au/media/fydjqofh/australian-energy-council-solar-report-q12024.pdf

And of course I can’t help but boast:

Data from the Clean Energy Regulator shows Queensland has hit a huge milestone in 2023 – hitting one million rooftop solar installations since records began, beating out every other state in the country.

Stephanie Gray, from the Queensland Conservation Council, says that this is a testament to smart government rebates to drive down the price of the technology.

“Rooftop solar plays a very important role in Queensland’s energy mix now with an impressive 5.9 GW of installed capacity – that’s three and a half times the capacity of Queensland’s largest coal-fired power station,” she said.

“Solar in Australia is a success story that demonstrates the power that governments have to make clean technology more accessible to all.”

https://reneweconomy.com.au/sunshine-state-milestone-as-queenslanders-install-one-million-solar-rooftops/ https://www.queenslandconservation.org.au/qld_reaches_solar_milestone

I know it’s real easy and cool to be a doomer but we have been making progress, we just have to hope labor gets back in 2028 to keep making progress

0·14 days ago

0·14 days agoTo be fair SA does around 2-3gw at peak and QLD does 8-10gw, so fair shake a bit more solar required for Queensland

1·17 days ago

1·17 days agoIsn’t labor tackling that though?

AFAIK it’s because there’s not that much money to be made with large scale solar in Australia, when like 3/4ths of the year the wholesale price of electricity is negative due to too much solar there’s not much incentive to build it, the money is in grid firming now (battery/hydro/wind/etc)